- Home

- Michael Blair

If Looks Could Kill Page 2

If Looks Could Kill Read online

Page 2

“A driver no less?” I said, looking at Carla. She gave me a wry smile.

“You ever done any skiing on Blackcomb Glacier?” Ryan asked.

“Horstman,” I said.

“What?”

“There’s no summer skiing on Blackcomb Glacier,” I said. “Only on Horstman Glacier.”

He shrugged it off. “Whatever. It’s not important. Probably won’t have time anyway. I’m working on a deal that will really put the place on the map.”

“Whistler seems to have done all right so far,” I said.

Ryan laughed his unpleasant laugh. “All right may be enough for some people,” he said, “but not for me.”

A massive blond beach boy type joined our little group, about doubling its size.

“Sam,” Ryan said. “Where the fuck’ve you been?”

“Sorry, Mr. Ryan,” Sam replied easily, offering no explanation.

“Those are ours,” Ryan said, pointing to a stack of matching luggage beside the carousel. Sam loaded the bags onto a cart and headed toward the exit.

Ryan nodded curtly to me and took Carla’s arm.

Carla, momentarily resisting, said, “It was good to see you again, Tommy.”

“Wait,” I said.

She stopped and turned, Ryan’s hand still on her arm.

I had spoken impulsively, with no idea of what I was going to say. There wasn’t anything to say, I realized. Not now. “Nice to see you too,” I said.

Ryan pulled her almost roughly toward the exit.

I held my breath, bracing myself for the crush of disappointment, for the same profound loss I’d felt two years ago when she’d disappeared without a word. When it did not come, I let the air leak slowly out of my lungs. I felt a peculiar sense of relief, as if I’d just awakened from one of those vividly real dreams in which a tooth has fallen out or I’d started smoking again. Carla had messed up my life once, and once was quite enough, thank you. As interesting as the wrapping was, I didn’t need the hassle that came with the rest of the package. Nevertheless, I could feel the spot on my cheek where she’d kissed me and the heavy musk of her perfume still lingered in the air.

“Daddy?” Hilly said.

Mentally shaking myself, I said to Hilly, Beatrix and Harvey, “All right, troops, let’s hustle.”

Chapter 3

It took teamwork, but we finally managed to get Harvey into the back of my old long-bodied Land Rover, wedged between Hilly’s suitcase and the heavy steel equipment case I’d had bolted into the rear cargo space. Harvey still didn’t seem to be aware of Hilly’s furry little pal, even though the ferret kept peering over Hilly’s shoulder at the dog. I wondered if ferrets had multiple lives like cats.

“You should zip Beatrix into her bag,” I told Hilly as we pulled out of the airport parking lot. “I don’t want her getting underfoot while we’re driving.”

“But she likes looking out the window,” Hilly said.

“At least put her on a leash,” I said.

“I don’t have one.”

In the luggage space, Harvey sat up, his huge grey and black head looming in the rearview mirror. Beatrix beat a hasty retreat into Hilly’s jacket as he laid his head on the back of the seat.

“Does your mother know you smuggled her onto the plane?” I asked.

“No. She thinks I left her with a friend. You won’t tell her, will you?”

“No,” I said. “I won’t tell her. How did you manage it, anyway?”

“Inside my shirt.”

“Is she housebroken?”

“Well, she kind of uses kitty litter, most of the time. She’s still in training.”

“Wonderful.”

She reached into the side pocket of Beatrix’s bag, took out a small hardcover book with a photograph of a very cute ferret on the cover, opened it and started reading silently to herself.

The Saturday afternoon traffic was light and we made good time, aided by some luck with the lights on Granville. At 16th Avenue, I turned right off Granville, then left onto Hemlock. As we approached the lights at Hemlock and Broadway I spotted a pet store in the small shopping centre at the corner. Lucking into a parking space, we left Harvey in the Land Rover, barking and slobbering on the windows, while Hilly and I went into the store. Over Hilly’s protests I selected a cage large enough to give Beatrix some room to move around, a litter pan that fit inside, a bag of litter, a drinking bottle, and other paraphernalia to make Beatrix a home away from home. I also bought a harness and leash so Hilly could take Beatrix for walks or whatever one did with a ferret.

“Beatrix doesn’t like cages,” Hilly said again as I loaded the cage into the back of the Land Rover.

“Neither do I,” I said, “but until she’s completely housebroken I’m damned if I’m going to give her free run of the house.”

“That’s not fair.”

“Perhaps not,” I agreed, “but that’s the way it’s going to be.”

I opened the passenger door for her and she threw herself into the car, scowling darkly. She was still sulking a few minutes later when we swung under the six-lane span of the Granville Bridge approach and drove between the massive bridge piers onto Granville Island, a renovated industrial area in False Creek, the narrow inlet that separates the southern sections of Vancouver from the downtown core. I lived in Sea Village, a community of a dozen or so floating homes moored two deep along the embankment between the Granville Island Hotel marina and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. My house was a registered vessel called Enterprise, of all things, owned by Howie Silverman, an old friend and real estate developer (and Star Trek fan) who’d retired to Israel, to the frustration of Revenue Canada. It resembled a New England two-storey wood-frame cottage transported west and installed on a reinforced concrete hull, except that the clapboard was forest green and the roof was flat and surrounded by a cedar railing. I paid a nominal rent, plus the taxes, mooring fees, utilities, insurance, and maintenance. I might have been able to live more economically elsewhere, but Granville Island was a lively and interesting place, although in the summer sometimes a bit too lively. And it was a two-minute ferry ride across False Creek to the dock at the foot of Hornby Street, from where it was an easy walk to my studio at Granville and Davie.

I parked the Land Rover in my reserved slot next to the boardwalk and unloaded Harvey and Hilly’s luggage. The tide was out and Sea Village’s main floating dock, which runs parallel to the embankment, was fifteen feet below the level of the boardwalk atop the embankment. Harvey looked uncertain as I led him down the steeply sloped ramp onto the dock, which I was sure sank slightly under his weight. I wondered if dogs were susceptible to motion sickness. Some people, my mother among them, find the constant slow movement of the docks and the floating homes disturbing, although my father insists it’s all in her head. But Harvey seemed to relax as soon as he was surrounded by the walls of Maggie Urquhart’s house.

“Was he any trouble?” Maggie asked as she unclipped the leash from his collar.

“None at all,” I said.

Maggie was about fifty, petite and slim, with quick dark eyes, thick grey-blond hair cut boyishly short, fine bone structure and a firm, flawless complexion. A professor of anthropology at UBC who had written an international best seller a few years ago about urban spiritualism or something that had made her comfortably well-off, she and Harvey had moved into Sea Village about six months ago. She was taking a sabbatical to write another book and had offered to keep an eye on Hilly from time to time.

“I really appreciate your picking him up,” she said.

“It’s the least I can do,” I said.

“Still,” she said, opening a fat red nylon wallet. I thought for a moment that she was going to try to give me money, but she unzipped a compartment and took out a purple and black business card. “Maybe I can do your chart.”

“My chart?” I said. She indicated the card. There was a complex wheel symbol in the corner and the text read Maggie Urquhart

, Astrologer. “Ah,” I said. “My chart.”

* * * * *

“Hilly, don’t give me a hard time about this,” I said as we unloaded Beatrix’s new cage from the Land Rover. I put it into the communal wheelbarrow the residents of Sea Village use to transport groceries and such down the ramp onto the docks. “I’ll bet your mother doesn’t give her free reign in her house.”

“She makes her live in a cage in the basement,” Hilly answered resentfully.

“I’m surprised she even let you keep her.”

“The school shrink said it would be good for me to have a pet, teach me responsibility and all that dreck.” Hilly made a face. “Mom wanted me to get fish. Fish aren’t pets, they’re pet food.”

“What about a cat? Cats are nice. Or a dog.”

“Boring. Besides, the jerk’s allergic to dogs.”

“The jerk?”

“Mom’s husband,” she said with a disparaging sneer. “My ugly stepfather. The Fat Food King.”

“Ah, Jack.” Jack Flynn was my ex-wife’s husband. He owned a chain of fast food franchises around Toronto and made buckets of money. I suppressed a guilty thrill of satisfaction that Hilly didn’t like him. I had met him only once and he had seemed to be an okay guy, but he was, after all, married to my ex-wife and for the last five years had played a larger part in my daughter’s life than I had. “And he’s not allergic to Beatrix?”

“She hypno-allergic.”

“That’s hypo-allergic, I think.”

“Whatever.”

“I’ll make a deal with you,” I said. “Until Beatrix gets used to the place, she lives in the cage with her litter pan. Once she’s proved she’s trained to the litter, she can come out. But only when you’re around to watch out for her. And,” I added, “the ferret on the cover of your book has a bell on its collar. I think that’s a good idea. Keep her from getting stepped on.”

“I have a collar like that, but she doesn’t like it.”

“She’ll get used to it. Do we have a deal?”

“I suppose,” she agreed grudgingly.

“Good,” I said. “All right, let’s get this stuff put away. Your grandparents will be here soon.”

Hilly’s huge suitcase almost got away from me on the ramp. It was probably waterproof, but I was relieved I didn’t have to fish it out of the harbour. Daniel Wu was out on his roof deck, tending his forest of plants. Daniel was an architect, sixty-odd, about five feet tall, and owned the biggest house in Sea Village, directly across the dock from mine. Hilly adored him.

“Daniel,” Hilly called, waving. Daniel waved back. “Daddy, can I go introduce Beatrix to Daniel?”

“Sure,” I said. “But put this on her first.” I helped her fit Beatrix with the harness we’d bought and attached the leash. Beatrix twisted herself double and bit at the harness.

“She doesn’t like it,” Hilly said.

“She’ll get used to it,” I said.

“Daniel, can I come up?” Hilly called up to Daniel.

“You certainly may,” he called down. “The door’s open.”

Hilly went to visit with Daniel while I lugged her suitcase, the cage, and the rest of the stuff into my more modest dwelling. My parents would be arriving within the hour and I had to get dinner started, so I just left everything in the hall and went into the kitchen. Yes, I know, boats have galleys, not kitchens, and some of the residents of Sea Village insist on calling their kitchens galleys, but as far as I’m concerned floating homes are houses, not boats, notwithstanding that they must be registered as such. Some people call them houseboats, but they aren’t. A houseboat is an actual boat, in form and function, with a motor and a pilot house and you can unhook it from the utilities and a-sailing go. My house, on the other hand, wouldn’t have looked out of place in any mainland neighbourhood, except maybe for Maggie Urquhart’s 18-foot Boston Whaler parked in the slip between her house and mine.

I started laying things out on the stainless steel countertop. I’d planned the menu days earlier, had got in everything I’d need – normally my cupboards made Old Mother Hubbard look like a hoarder. I liked to cook, even liked to think I wasn’t half bad at it – at least I hadn’t killed anyone – but I didn’t get much joy out of cooking for myself, so when I got a chance to display my stuff, I tended to go all out. Hanging on a hook on the inside of the pantry door was the funny apron Carla had given me. It was the only gift I’d ever got from her. On a whim, I put it on. I’d never used it and it was stiff with starch and newness. On the front was an enlarged replica of an Emergency Poison Control sticker.

For a long time after Carla left, whenever I closed my eyes I saw her face, felt the smooth silken touch of her against my palms, remembered the taste of her, the delicate scent of her skin and her hair. I got over her slowly, but I got over her. At least I thought I had.

I had a little time to spare so, feeling masochistic, I went upstairs to the small spare room I used as a TV room and home office. I opened the bottom drawer of the file cabinet and took out a brown manila folder. The folder contained a dozen eight-by-ten black-and-white photographs and an equal number of three-by-five colour prints I had taken of Carla. The black-and-whites were studio shots, stark lighting accentuating her moonlight-pale skin against the light-absorbing black seamless backdrop, so that she appeared to float weightless in a starless space. Even though it had been her idea, she’d been nervous at first, uncomfortable about posing nude (but not half as nervous or uncomfortable as I’d been) and her earlier poses had been artlessly immodest and wouldn’t have looked out of place in Penthouse Magazine. Soon she’d begun to relax, though, to forget about the camera, about me, focusing inwardly. And I’d cooled down enough to think about lighting and composition, contour and texture and contrast.

The colour photos had been taken on a summer’s day in Stanley Park, by the big fresh-water pond called Lost Lagoon, and on Prospect Point, with the dark arc of the Lions Gate suspension bridge in the background. They were just casual snaps, but as I flipped through them my chest filled with an icy white heat that made breathing difficult. In the colour prints she was real, a flesh and blood and bone human being, not the unearthly creature in the black-and-whites, cool and soulless and distant.

She was radiantly, exquisitely, breathtakingly beautiful and it had been a source of constant wonderment that she’d loved me.

But she hadn’t, of course.

I tossed the photographs back into the drawer and went downstairs to shell shrimp.

Chapter 4

“I don’t know why you insist on living here,” my father said, stirring his Scotch-rocks with his finger. “For what it costs you to live here you could buy a condo in Kitsilano or Point Grey. You’re not building any equity either. You should think about your future.” Dad was sixty-three and had worked for the same engineering firm since graduating from Queen’s University at age twenty-four. Three years ago he’d taken early retirement to devote himself full time to managing the modest stock portfolio he’d built.

“Forty,” I said as I went on shelling shrimp.

“Eh?”

“I’ll start thinking about my future when I turn forty,” I said. Truth be known, however, I’d been thinking about my future since I’d turned thirty. I just hadn’t done much about it, except quit my job at the Vancouver Sun to start my own photography business, a decision I occasionally but only mildly regretted. I’m not the entrepreneurial type, don’t really have the hustle. I liked the freedom, though, so it was a worthwhile trade off.

“You’re what?” Dad said. “Thirty-eight?”

“Seven.”

“When I was thirty-seven I’d already paid off the mortgage on our house.”

“Which you probably immediately re-mortgaged to invest in some crazy scheme – ”

“I never took chances with the roof over our heads,” he said. “I had a responsibility to your mother and you kids.” He sipped his drink. “With careful management your mother and I won’t bec

ome a burden on our children in our later years.”

“I thought you always intended to be a burden on your children,” I said. “We owed you, you said.”

“You do,” he agreed. “But at the rate you’re going, you’ll never be able to afford it.”

“How about Mary-Alice? She’s got plenty of money. Or David has, at least.”

“Christ, my son-in-law the proctologist,” Dad said with a snort of disgust. “She could at least have married a real doctor. It’s bad enough he’s damned near as old as I am.”

And damned near as stuffy, I added to myself. Of course, what could you expect from a man who’d spent the best part of his adult life peering at people’s nether regions? When I’d told Linda, to whom I was still married at the time, that my little sister was going to marry a proctologist almost twice her age, her only comment had been a dry, “Bummer.”

I finished shelling the shrimp, put them in the refrigerator, and wiped my hands on paper towel. “Refill?” I asked, pointing to Dad’s drink.

“Uh?” He seemed surprised his glass was empty. “Sure.” He handed me the glass.

My mother came into the kitchen and Dad’s expression turned stony.

“Is Hillary still next door with that man?” my mother asked.

“Yes, she is,” I replied. I heard the edge of irritation in my voice, but if my mother noticed it, she chose to ignore it. I handed my father his drink and punched a button on the kitchen phone. It dialled Daniel’s number. When his machine picked up, I hit the pound sign button to by-pass his outgoing message and said, “Daniel, would you send Hilly home, please? Her grandparents are here. Thanks.” I hung up.

“I don’t know how you can let her stay alone with that man,” my mother said.

My father said, “His name is Daniel, for god’s sake.”

Mother ignored him. He took his drink into the other room.

In the early fifties, before meeting and marrying my father, my mother had been a runway model and B-movie actress. I’d seen photographs of her and she had been a very lovely woman, cool and elegant and graceful. While it’s difficult for a son to be objective about his mother without twinges of Oedipal guilt, she was still attractive, although sometimes it was hard to tell through the pancake, rouge and eye-liner. Time and gravity, though, as well as two children, had taken a toll. She wasn’t obese, but she wasn’t exactly slim either. And she dressed as though she still weighed a hundred and ten pounds, in close-fitting garments that emphasized her plumpness and severely strained the containment limits of Lycra.

The Evil That Men Do

The Evil That Men Do The Dells

The Dells Hard Winter Rain

Hard Winter Rain Depth of Field

Depth of Field Overexposed

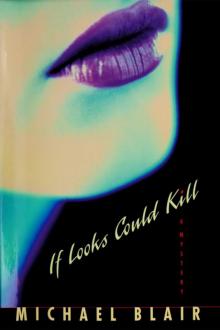

Overexposed If Looks Could Kill

If Looks Could Kill