- Home

- Michael Blair

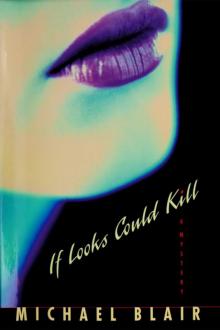

If Looks Could Kill Page 4

If Looks Could Kill Read online

Page 4

I left Hilly and Bobbi to get reacquainted while I went into the main studio and started coffee. Bodger was asleep in my office, curled up in the fancy ergonomic executive chair that had been a parting gift from my co-workers at the Sun. He hissed at me when I tried to roust him, so I rolled the chair to the window and dragged another over to the desk. I stared out the window for a moment, at the blank wall of the old Hotel California across Davie. The building now housed a Howard Johnson’s and the mural of the fifty-foot blue-jean-clad blonde that had adorned the wall had been painted over. I missed her and made a mental note to print up some of the shots I had taken of her over the years since I had moved into the studio. Then I woke up my computer and started working on the bid to do the photography for Western Air Services’ annual report.

Half an hour later Bobbi knocked on the door frame. Without waiting for an answer, she came in, picked Bodger up and sat in my chair, cuddling him in her lap. He purred loudly as she stroked his chewed-up ears.

“Bloody cat,” I said. “Why do I tolerate him? He hates my guts and he hasn’t caught a mouse in I don’t know how long. You feed him too much. Look, he’s getting fat as a pig.”

“Boss,” Bobbi said, “I’ve seen you feeding him those treats you keep in your drawer.”

“Bribery is the only way I can get him out of my chair. And quit calling me boss.” Although she’d been with me since I’d started the business six years ago and was now more friend and partner than employee, I couldn’t get her to stop calling me Boss.

“Sorry. Can we talk?”

“Sure. What’s up?”

“It’s about the Pacific Hotels thing. I feel awful about it. I was certain I put the E6 card back in the processor after I used it.”

The Wing-Lynch film processing machine I had bought second hand when I had started the business had two program control cards: an E6 card for processing colour transparencies – that is, slide film – and a C41 card for processing negative film for colour prints. The cards fit into a single slot in the front of the processor, which was about the size of a small refrigerator. To switch between negative and transparency film processing, you had to pull out the C41 card and replace it with the E6 card. Mostly we worked in transparency, but for some of our smaller clients and most portrait work we shot colour print film. Someone, either Ron or Bobbi, had forgotten to change cards when we processed the Pacific Hotels job, which we had shot on transparency. If you use the right film, the right exposure settings and avoid certain subject matter colours, you can achieve some interesting creative effects developing slide film using the C41 process, but for our purposes the films had been ruined.

“Don’t beat yourself up about it,” I said, with perhaps more charity than I felt. “These things happened. Is the new stuff ready yet?”

“I just sent it down to be scanned.”

More and more, both existing and prospective clients were demanding electronic files rather than film. I knew if I wanted to stay in business much longer, I was going to have to bite the bullet and go into hock to switch to digital; however, I intended to put it off as long as possible. So far we were managing by having transparencies scanned to CD ROM disc by a service bureau, although it was eating into our already slim margins. But why had Bobbi sent the work out? That was Ron’s job. I asked her.

“He said he was too busy,” she said.

“With what?” I wondered aloud.

She shrugged.

“Right.” Bodger jumped down from her lap, stretched, and sauntered out of the office. Maybe I should let Hilly bring Beatrix to the studio, I thought. Teach the bugger some respect. I had to start somewhere. “When are your rock ‘n’ rollers coming in?” I asked.

“About three.”

“What are they called again? The Scum?”

“The Sluts,” she said. “Nice girls. It was a fun shoot.”

“I bet.”

“I’m not sure if I’d call the stuff they play music,” she said, “but the kids like it. Their first CD sold pretty well wherever they played. Hilly’s listening to it now.”

“If she dies her hair green and red and starts wearing black combat boots,” I said, “I’ll know who to blame.”

“Not me,” Bobbi said with a laugh. “These girls dress more like that little hooker who hangs around downstairs.”

“Oh, swell.”

The phone in the reception area rang. Mrs. Szymkowiak, my part-time receptionist/bookkeeper wasn’t in yet, so I intercepted it from my extension.

“Tom McCall,” I said.

“Tommy? It’s me. Carla. I need to see you.”

Chapter 6

I wanted to say no. I really did. My brain even sent the signal to my mouth, but what came out was, “Where are you?” Perhaps some other organ had taken control.

“I’m downtown,” she said. “Around the corner from the place you bought me breakfast that first time.”

“I have an appointment with a client near there at ten. I could meet you later, I suppose, say around eleven.”

“I was hoping to see you sooner than that,” she said.

“Come here then,” I said.

“No, that wouldn’t be a good idea. Could you meet me before your appointment? It won’t take long.”

“What won’t take long?” I asked.

“I’d rather explain in person.”

“Not even a hint,” I said. “Should I check my insurance coverage?”

“Tommy, please.”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll meet you in the coffee shop of the Pacific Palisades Hotel at Robson and Jervis in half an hour.”

“Thanks, Tommy,” she said and hung up.

I arranged with Bobbi to courier the CD of scanned images to Pat Jirasek, Pacific Hotels’ head of public relations and advertising, as soon as it was back from the service bureau, with a note that I’d talk to him later. Since I didn’t have enough time to go home to pick up the Land Rover, I asked her if I could borrow her VW Golf, but she told me it was in the shop. I took a cab.

All the way downtown I berated myself for not having the good sense to say no to Carla. Since running into her at the airport I’d taken out my memories of her, held them up to the light and examined them carefully. Even after two years it still made me squirm with embarrassment to remember what a complete idiot I’d been. But everyone was entitled to make mistakes. It was history now, though, time to close the book on that chapter of my life. Maybe I could do that today, over coffee.

When I first met Carla Bergman she was working as a singer with a cheesy lounge act called The Seven Ups, even though there were nine of them, if you counted the two girl singers. Music for every occasion – weddings, bar mitzvahs, grads, coming out parties (I didn’t know people still had coming out parties). They weren’t very good. In fact, they made Lawrence Welk sound like the London Philharmonic. Remarkably, though, they’d grossed a couple of hundred thousand the year before and were prepared to spend some of it to upgrade their image. Who was I to argue? They set up in the studio, donned their lounge lizard outfits, their manager loaded some tapes into my sound system – to help put them in the right mood, she said – and I began shooting. After a while I asked if I could turn the music off, that I found it distracting.

The music wasn’t half as distracting as one of the two girl singers in the group. A study in contrasts, both had probably been hired for looks rather than singing ability. One was bubbly and blonde and under any other circumstances I would have found her quite attractive. But the other literally took my breath away. She was lean and lithe as a dancer. Her coal-black hair was silken and slightly curled and her pale flawless skin had a subtle yellowish cast, like antique ivory. But it was her eyes – indigo, almond-shaped and tilted and set almost too far apart – that I noticed first. They bewitched me and I wasted a dozen shots because of them, unable to resist the compulsion to capture them on film.

During a break I collected my nerve and asked her name.

“Carla Bergman,” she s

aid in a soft husky voice that made my pulse race.

I asked if she’d ever done any modelling, trying to build up the courage to ask for her telephone number. She smiled, and said, no, she hadn’t, but it sounded interesting. Singing wasn’t exactly her thing.

I kept my opinion to myself. When she’d sung along with the tapes, her voice had had a thin, reedy sound and she’d had trouble making the higher notes. The other girl might not have been able to compete in the looks department, but she was the better singer, hands down.

When the shoot was over the manager wanted to talk about doing the same thing for another group she handled and by the time I was finished with her, The Seven Ups, Carla included, had packed up and gone. I quietly obsessed for about a week, thought about calling The Seven Ups’ manager and asking for Carla’s telephone number, but never did, then I more or less forgot about her.

Until one morning about three weeks later when she walked into the studio, told me she’d been fired and asked me if I’d been serious about the modelling. I told her that she certainly had the looks and the figure, but that modelling wasn’t something you could just take up, like pottery or scuba diving, that she needed to put together a comp and register with an agency if she really wanted to work. But, I added, if she wanted to discuss it I’d be glad to buy her lunch.

She accepted. Since I had an appointment downtown I took her to brunch at Benny & Dick’s, a tiny breakfast place occupying what had once been the front porch of an old house on Jervis, just above Pender.

“Why were you fired?” I asked her after we’d placed our orders.

She shrugged and said, “I suppose I could tell you it was because I wouldn’t go down on Jimmy, the band leader, but that would be only partly true. Let’s put it this way, if I had been willing to go down on him, he might’ve been willing to overlook the fact that I can’t sing. Not that I have anything in particular against oral sex, but besides not needing the job that badly, the guy’s a pig and a girl can’t be too careful these days.”

“You might have a case for a sexual harassment complaint,” I said.

“Except that he would just claim he fired me because I can’t sing, which is true.”

“You aren’t that bad,” I said.

She laughed. “Thanks, but I’m not that good, either,” she said with a shrug. She wasn’t wearing a bra under the thin cotton T-shirt and the gesture made interesting things happen. “Let’s face it, neither of us was hired for singing ability alone. At least April can carry a tune. I was thinking about moving on anyway. Did you mean what you said? Do you really think I could get work as a model. Or were you just bullshitting me? It wasn’t just a line, was it?”

“Not entirely,” I said.

“But still a line?”

“Well, yes,” I admitted. “It was an excuse to talk to you.”

“You didn’t need an excuse to talk to me,” she said. “I was hoping you would.”

My pulse quickened and I could feel the heat on my face. “But it wasn’t entirely a come on,” I said quickly. “You’re very attractive, you probably wouldn’t have too much trouble finding work, but there’s a lot of competition and looking good isn’t all there is to it. As I said, you’ve got to be represented by an agency and you need a comp. It helps to have a good portfolio too.”

“What’s a comp?”

“A brochure with sample photographs of yourself, showing different styles and moods. Plus your specs: measurements, sizes, and so on. Advertising.”

“And the portfolio?”

“Examples of work you’ve gone.”

“How do I go about getting a comp?”

“If an agency agrees to represent you, they might do it for you. Some will deduct the cost from your first few jobs, others will charge you. If you can afford it, you could hire a photographer and do it yourself. Design-wise, they’re fairly straightforward, but it would probably be a good idea to have a graphic artist lay it out for you.”

“Could you do it?”

“Me?”

“You’re a photographer.”

“Yes, I know. But I don’t do much fashion work. I don’t do any fashion work, actually.”

“You hire models don’t you?”

“Yes, but the models we use are more like extras in a movie. Bodies. People standing around hotel lobbies or riding chair lifts on a ski hill. What you want is someone who can make you look like a Vogue model, not a guest in a hotel or a diner in a restaurant.”

“Is it expensive?”

“It can be,” I said. “I wouldn’t advise you to do it on the cheap, though,” I added. “You get what you pay for.”

She said, “I don’t have much money.”

The food arrived, ham and eggs and home fries for her, one of Benny & Dick’s huge blueberry pancakes for me. She attacked her food as if she hadn’t eaten in a week.

“How long has it been since you’ve eaten?” I asked.

She swallowed. “About a day and a half, I guess. Sorry. I hope I’m not embarrassing you.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said.

We ate in silence, until she’d finished her meal, plus what was left of mine. This time I wouldn’t be making my usual contribution to the local food bank, the penalty exacted by Benny and Dick for leaving food on your plate.

I got us more coffee from the thermos on the counter by the kitchen. Sitting down, I asked, “Do you have any money at all?”

“No,” she said, holding her fingertips over her mouth as she belched inaudibly. “I spent my last thirty dollars on a room last night.”

“So you don’t have a place to stay.”

“No,” she said. “But I’ll be all right.”

Before I realized what I was saying, I said, “I have a spare room you could borrow.”

She looked at me for a long time before speaking. “I don’t know,” she said.

“If you’re worried, there’s a lock on the door,” I said. “You’d be perfectly safe. Besides, I’m not the dangerous type.”

“It’s not that,” she said. “I can take care of myself. But I wouldn’t want to put you out. You probably have a wife or a girlfriend. How would she feel about me camping out in the spare room?”

“No wife,” I said. “No girlfriend either, so there’s no problem.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yes, I’m sure.”

“Well, all right, if you’re sure. But only for a little while,” she added. “A couple of weeks at most, until I find a job or something.”

“That’s fine,” I said.

So she moved in with me.

And for about a week she actually slept in the spare room.

Chapter 7

I’d been waiting for almost half an hour, had drunk two cups of insipid coffee and turned down a third, and was within seconds of leaving, when she finally made her entrance. There was no artifice, no pausing, adjusting, looking around, spotting her target, and waving. It was more subtle than that, and less. It was as if the room suddenly filled with an electrical charge. Zap. It turned the head of every man in the room, and the heads of a few of the women. And she’d dressed for effect, in a slightly flared wrap-around skirt that came to mid-thigh and white raw silk blouse that drifted across her breasts like smoke. She carried a large shoulder bag.

My stomach knotted. I didn’t know if it was with apprehension or desire. Perhaps it was both. I stood and she kissed me on the cheek. Her lips were cool and waxy with lipstick, but they left a spot of heat on my cheek, like a gentle brand. I resisted the urge to rub it.

“Thanks for coming, Tommy,” she said as she sat down.

I hated being called Tommy, but I didn’t say anything. It had never done any good anyway. No matter how many times I’d told her I preferred Tom or Thomas, she’d persisted in calling me Tommy.

“What was so important it couldn’t wait an hour or so?” I asked.

“Would you order me a cup of tea?”

I signalled the waitr

ess and placed the order.

“So, what is it you need to see me about?” I asked. I winced inwardly at the adolescent whine in my voice.

“Can’t we take a few minutes to get acquainted again?” she said.

I shook my head. “You’re unbelievable,” I said. “More than two years and not a word. Nothing. For all I knew you were dead. I even thought about hiring a detective, but I couldn’t afford it. And now you want to get acquainted again. Jesus. Do you have any idea how angry I was with you? Angry is an understatement. I was in love with you, for god’s sake. I’d have given you anything you wanted.” Her blue eyes were steady. “What happened? Why did you leave like that?”

“There were just too many strings attached,” she said. “I’ve never liked strings.”

“Don’t give me that,” I said. “If there were strings, they were yours, not mine.”

“I couldn’t live up to your expectations,” she said.

“Where are you getting this stuff? Strings. Expectations. C’mon, Carla. I never put any conditions on our relationship.”

“You seriously expect me to believe you did all those things, spent all that money on the comps and the modelling classes, without expecting something in return?”

“No, of course not,” I said. “I’m no saint. I didn’t expect to get stabbed in the back, though.”

“I’m sorry I let you down.”

“You didn’t have to steal from me,” I said in a voice that sounded petty and aggrieved even to me. When she’d left she’d taken my stereo – an NAD receiver and CD player with Mission speakers – a new Macintosh laptop computer and a Hasselblad camera with motor drive and portrait lens. “The camera alone was worth five thousand dollars.”

“It was broken,” she said. “I didn’t get anywhere near that much for it. Besides, you were insured, weren’t you?”

“Of course, but I had a hell of a time collecting. It’s a good thing for you the insurance agent was a friend of mine, otherwise I’d’ve had to report you to the police or the insurance wouldn’t have paid off.”

“Why didn’t you report me?”

The Evil That Men Do

The Evil That Men Do The Dells

The Dells Hard Winter Rain

Hard Winter Rain Depth of Field

Depth of Field Overexposed

Overexposed If Looks Could Kill

If Looks Could Kill